Baseball has always been my favorite sport, continuously finding a way into the meaningful periods of my life. When I was a kid, we joined the masses of kids collecting untold numbers of unopened TOPs cards and collector item rookie cards in plastic cases. After our dad passed, my older brother Brian would come back from college and we’d head to the local park to play catch—myself a high school athlete and Brian still with a stronger arm despite not having played the sport in a decade. After he was diagnosed with ALS, we sat through two rain- soaked games to watch our adopted home team (Nationals) play our new local hometown Cubbies. In September 2020, my wife and I bought our first home a mere 200 yards from The Bleachers at Wrigley Field.

But as kids in the 90s around DC, nothing was more synonymous with baseball than the eventual new Ironman, Cal Ripken Jr, so you can imagine my excitement on that legendary night of September 6, 1995: Dad & I sat in Camden Yards among the 46,000 fans watching Cal Ripken break Lou Gehrig’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games.

Joining us to witness history were President Clinton and baseball royalty: Ernie Banks, Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson and Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio. As Cal trotted around the stadium, it seemed that the entire city of Baltimore was celebrating. But it was bigger than that. Everyone in baseball was celebrating Cal Ripken breaking the untouchable record held by Lou Gehrig.

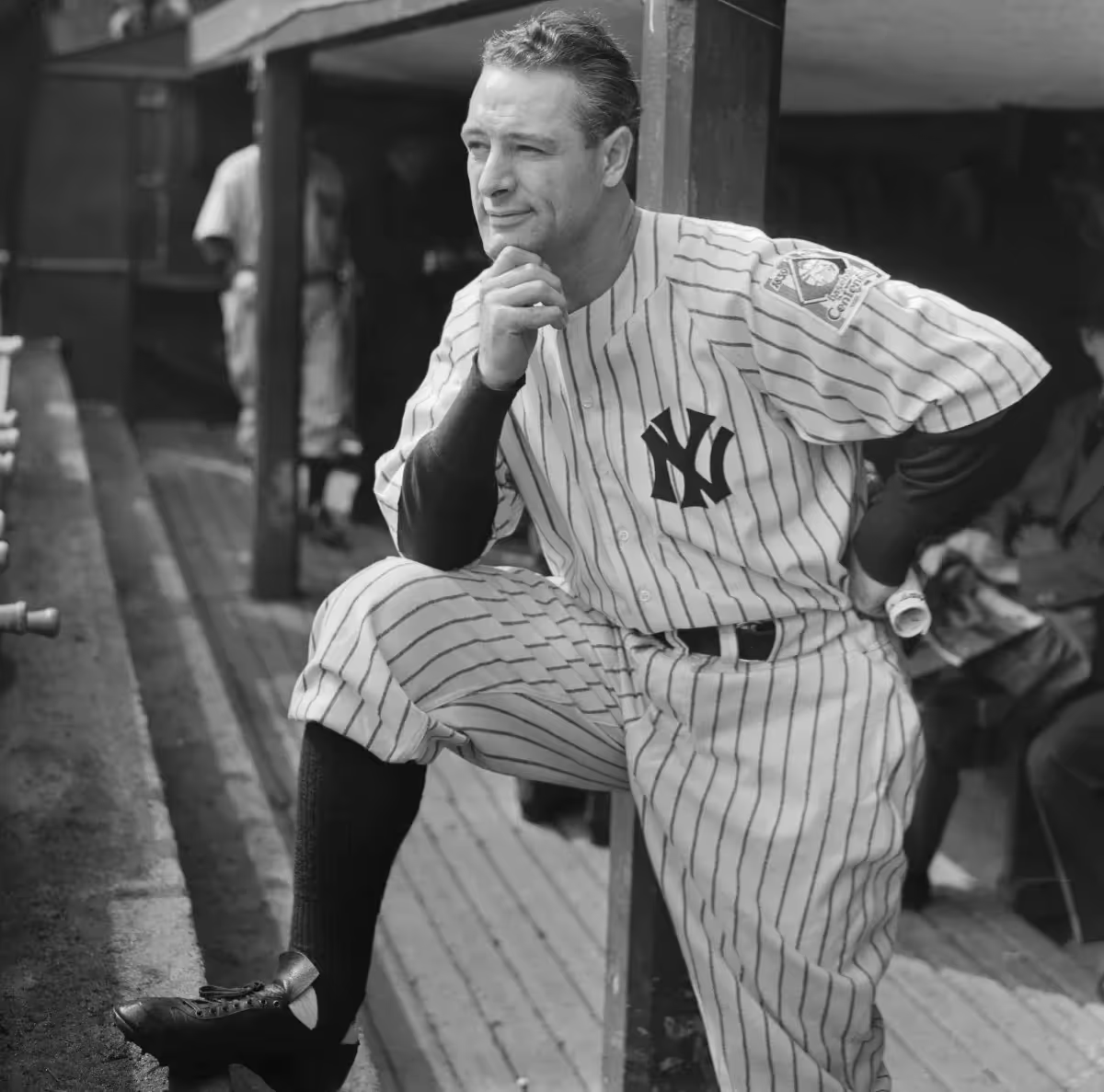

As a boy, I knew who Lou Gehrig was, an echo from the past, the Iron Horse, the Hall of Famer. I knew of his legendary swing, and the power emanating from the tree trunks of legs. But little did I know how our paths would intertwine…

Lou Gehrig Day in MLB

MLB has designated June 2nd as Lou Gehrig Day, a day to raise awareness about amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the fatal neurodegenerative disease that abruptly ended Gehrig’s Hall of Fame career.

“Through Lou Gehrig Day, MLB will celebrate the groups and individuals who have led in the pursuit for cures, honor those who are bravely living with ALS, and remember all those whose lives have been lost to this disease.”

Decades after Gehrig’s death, famed LA Times sports columnist, Jim Murray, described Lou Gehrig's power, prowess and physique:

“I don’t suppose I ever saw a better baseball player than Lou Gehrig. But he was more than a player. He was a symbol of indestructibility. He was Gibraltar in cleats, a mass of muscular power. He looked immortal.”

If ALS can strike the indestructible immortal of Lou Gehrig, it can strike anyone, at any time. You have a 1-in-300 chance of being afflicted in your lifetime. Neither his young age, athleticism, nor his healthy lifestyle protected Gehrig.

But there is hope. Recently diagnosed with ALS, 30 year-old MLB researcher and writer, Sarah Langs said: “Baseball is here to try to end this disease.”

The History

Most people know of Gehrig's prowess as a major league Hall of Famer, but many don’t realize he was a two-sport athlete in college, attending Columbia on a football scholarship. Much like Bo Jackson, Gehrig knew football… and baseball. On the gridiron, he played both fullback and defensive tackle—without a helmet. On the diamond, his skills were matched only by his work ethic. The New Yorker reported: “he would practice hitting balls until it was too dark to see.”

On the day Yankee stadium opened in April 1923, Yankees’ scout Paul Krichell wasn’t there for the inaugural pitch. Instead, he was watching Gehrig, a dominant southpaw on Columbia’s baseball team, strike out 17 batters, and hit two homeruns in three at bats. When Gehrig wasn’t eviscerating opposing batters, he was destroying opposing pitchers’ ERAs. That sophomore season, Gehrig hit .444 with 7 homers in 19 games. Two months after Gehrig’s last college game, the Yankees scooped him up for $400 a month plus a $1,500 signing bonus.

The Stats

Gehrig broke into the big leagues in 1925. On June 2nd, Gehrig stepped into the line-up as the starter at first base and Wally Pipp never saw a Yankees’ line-up card again. The Iron Horse went on to play 2,130 consecutive baseball games in pinstripes.

Gehrig’s famous nickname, the “Iron Horse” was given to him by a reporter as an ode to the power and durability of the steam locomotive trains of the 1880s.

“Gehrig certainly is one of the Yank’s prize locomotives—a veritable Iron Horse to pull the team along with over the grades.

But the Iron Horse wasn’t just durable, many baseball writers believe Gehrig is the greatest first-baseman ever to play the game. His stats:

- .340 BA, .447 OBP, 1,990 RBIs; 1.080 OPS

- 493 HRs, 163 triples, 534 doubles and .632 SLG

- MLB record of 23 grand slams in a season

- 13 consecutive seasons with 100 RBI and 100 runs scored

- 7 seasons with a combined 200 hits and 100 walks

- 12 consecutive seasons of hitting .300

- 10 seasons of 30+ HRs

- First player in the 20th century to hit 4 HRs (nearly five) in one game

- AL record of 184 RBIs in one season

- Seven-time All-Star (‘33-’39) (MLB didn’t start All-Star game until 1933)

- One Triple Crown and two MVPs (‘27 & ‘36)

Despite playing most of his career in the shadow of Babe Ruth, Gehrig ranks third all-time in slugging and OPS, fifth in on-base percentage, and sixth in RBIs. As ESPN’s Tim Kurkjian astutely reported: “Of the top six RBI seasons of all time, Lou Gehrig had three of them. In 1927, hitting behind Babe Ruth, who hit 60 homers that year, Gehrig drove in 175 runs.”

The Final Season

In May 1938, Gehrig started his 2,000 game. But as the summer progressed, Gehrig’s chiseled body appeared to be breaking down. He changed his batting stance and swing, relying more on his hands and arms to punch the baseball rather than using his powerful legs to drive it for extra base hits. Singles replaced home runs. His drop-off in power led some to speculate that Gehrig’s age and the streak were catching up with him. But a baseball writer for the New York Sun thought differently:

“I’ve seen players go overnight, but I think there’s something deeper than that in Lou’s case. He takes the same old swing, but the ball doesn’t go anywhere.”

This was the first sign of ALS destroying Gehrig’s motor neurons, the nerves that send the brain’s signals to the muscles, telling them to move.

Gehrig finished the 1938 season with decent numbers for any other player, hitting .295 with 29 HRs and 114 RBIs. However, neither the off-season nor spring training remedied the slump.

In spring training, DiMaggio watched in amazement as Gehrig swung at—and missed—19 straight fastballs in batting practice:

“[T]he kind of pitches that Lou would normally hit into the next county… You could see his timing was way off... He had trouble catching balls at first base. Sometimes he didn’t move his hands fast enough to protect himself.”

Eight games into the 1939 season, everyone could see Gehrig wasn’t himself. By May 2nd, Gehrig was hitting just .143 and had only one RBI. He told manager Joe McCarthy to take him out of the lineup. No one ever saw Gehrig play major league baseball again.

The Diagnosis

On June 19, 1939, his 36th birthday, Lou Gehrig left Mayo Clinic with news that would seal his fate. The examination confirmed he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Instead of celebrating his birthday, Gehrig was left pondering how many birthdays he had left. The Mayo doctors gave him three years, at most.

On June 2, 1941—less than two years after his diagnosis—Lou Gehrig passed away. It was sixteen years to the day that he replaced Wally Pipp as the Yankees’ first baseman.

That is the story—both tragic and ironic—of why MLB chose June 2nd to become Lou Gehrig Day.

ALS: Eighty-two Years Later

Eighty-two years after Gehrig’s death, the outcome for those diagnosed with ALS is not much different than it was in 1941. The average lifespan is still 3-5 years and 50% of the population dies within the same short two-year timespan that took Gehrig’s life. Each year, approximately 6,000 Americans die of ALS.

Death is not just rapid, it’s cruel. ALS slowly paralyzes all the muscles in your body, depriving you of the ability to move, eat, drink, swallow, talk, and eventually breathe. Typically your mind stays intact, fully aware as you become trapped in your own body. There is no cure, and there are no disease-modifying treatments. People are sent home with a foreboding diagnosis.

Up until this last year, neurologists would often tell their patients, “I’m sorry but we can't help you.”

Brian wanted to change that. Like Gehrig, Brian was diagnosed with ALS at just 36 years old. But, Brian didn’t accept the status quo. “Six months after he was given six months to live,” Brian decided to fight.

First, he and his wife Sandra formed the non-profit I AM ALS, where their political expertise helped pass laws and expedite drug approvals. They didn’t stop there. Together they formed Synapticure to address gaps in health care that Brian and Sandra encountered when Brian was diagnosed.

Founded by a patient for patients, Synapticure’s model is built on a patient-centric telehealth practice with specialized neurological care for people with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, PLS and ALS.

Now 42 years old, Brian is still fighting for others while juggling his own diagnosis and ALS care. Recently Brian told PEOPLE:

"There are moments when I've thought, 'We've done a lot and it is time to step aside so someone else can be the face of this fight… but then I think about the friends I had in the beginning of the fight and how many of them have passed away, fighting until their last day. So I feel an obligation to keep fighting for them and for their families, because this has gone on for long enough. It is time to have the first ALS survivor."

So on Lou Gehrig Day, the baseball world will celebrate “The Iron Horse” not only for his achievements, but also to raise awareness about the disease that ended Gehrig’s Hall of Fame career at 2,130 games.

On June 2nd, our family will be honoring Gehrig, but we will also be celebrating my brother Brian for his tenacity and the change that he is bringing to Capitol Hill and clinical care alike. His undaunting determination mirrors that of Lou Gehrig.

Brian was diagnosed with ALS in August 2017. This month marks 2,130 days that he has been fighting ALS.

.png)