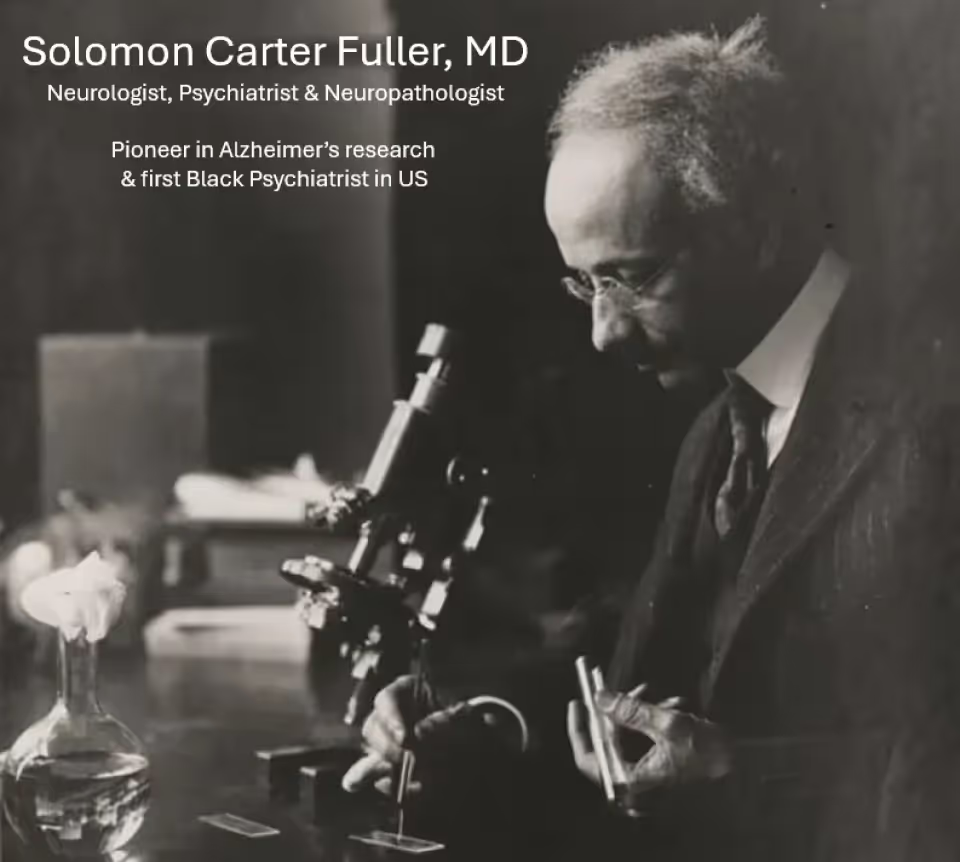

In honor of Black History Month, we want to celebrate the landmark research, career, and life of Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller. Commonly recognized as the first Black psychiatrist in the US, the often untold story is the pioneering role Dr. Fuller played in identifying the brain pathology that typifies Alzheimer’s disease. His work at the turn of the twentieth century is critical in helping African Americans who today are disproportionately afflicted with and dying of Alzheimer's disease.

The Early Life of Solomon Fuller, MD

Although his family had roots in America, Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller was born in Liberia in 1872. His grandfather, John Lewis Fuller, was born a slave in Virginia. A skilled shoemaker, he saved his money and purchased both his freedom and that of a white indentured servant who became his wife. The couple settled in Norfolk and had eight children, one of whom was Solomon Fuller Sr., the father of Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, Jr.

By 1852, racial persecution and deteriorating conditions in the Antebellum South became untenable. Utilizing the American Colonization Fund, John Fuller and his son Solomon fled to Africa, along with thousands of other free Black people hoping for better lives. In Liberia, the senior Solomon Fuller married Liberian-born Anna Ursula James, the daughter of two physicians and medical missionaries. They had a son who would grow up to be Solomon Carter Fuller, MD.

Solomon’s education was one of privilege. His mother home-schooled him and he became fluent in Latin by the age of 10. He then attended a private school run by Episcopalian missionaries, and at 12 years old he left home to attend a college preparatory boarding school.

As a teenager, the young Solomon triumphantly returned to his enslaved grandfather’s roots immigrating to the US to attend college and medical school. At first, he studied at Livingstone College, a historically black college1 in Salisbury, North Carolina. In the small town, Solomon reportedly experienced racism for the first time—something he had not known during his life in Liberia. Nonetheless, he persisted and received a bachelor’s degree from Livingstone in 1893.

In 1894, Solomon Fuller attended the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association and listened to an impassioned keynote address about the need to identify and understand the causes of mental illnesses. Impressed, Solomon Fuller decided to become a psychiatrist, ultimately receiving his degree from Boston University School of Medicine in 1897.

Early Career as a Neuropathologist

Following graduation from medical school, Dr. Fuller began a two-year internship at the Westborough Insane Hospital in Massachusetts. He excelled and was quickly promoted to a hospital pathologist in 1899. Here he first encountered employment discrimination: the hospital paid him $25 a month while paying a more recently hired white physician twice that amount. When he learned of this inequity, instead of a raise, Dr. Fuller negotiated for his own laboratory.

Concurrently, Dr. Fuller became a part-time professor at Boston University School of Medicine in 1899, where he was one of the first Black physicians to teach at a multiracial medical school. Boston University was one of the only medical schools to admit people of color, and seemingly ahead of its time. But it too paid him less than other white instructors.

During his internship and residency years, racism inadvertently redirected Dr. Fuller’s career path. As a Black man, he was assigned less clinical psychiatry work and more autopsies—a fairly uncommon procedure at the time. Though Dr. Fuller's autopsy work may have been borne in racism, it was transformed into a blessing. Those early years as a neuropathologist allowed him to analyze brain tissue from many deceased mental patients, often making discoveries that would eventually advance the fields of psychology and neurology, and open doors for him throughout his career.

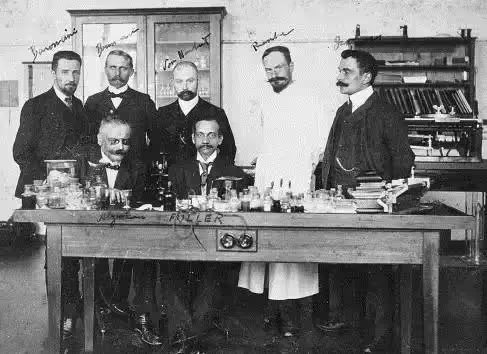

At the turn of the century, cutting-edge psychiatric research was taking place in Europe. Yearning to expand his academic and clinical prowess, Dr. Fuller was chosen as one of five graduate research assistants to study at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital at the University of Munich2. There he was privileged to learn from neuropsychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, whose 1883 book Compendium der Psychiatrie was the basic text for psychiatrists of the day.

Dr. Fuller’s landmark research accelerated when he worked with Dr. Aloysius (“Alois”) Alzheimer, a psychiatrist and neuropathologist who too had just begun working at the Kraepelin Lab. When interviewing applicants, Dr. Alzheimer reportedly turned away many others but chose Dr. Fuller because of his expertise as a neuropathologist.

The Discovery of Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer’s disease was first identified in the medical literature in the early 1900s. Dr. Alzheimer was treating a woman named “Auguste D.” At only 51 years old, she began having issues with memory, confusion, delusions, and hallucinations, becoming more fearful, paranoid, and aggressive. Ultimately, she was institutionalized. Decades later, the Lancet published Dr. Alzheimer’s clinical notes, which describe his examinations of Auguste D and sadly, chronicle her ongoing cognitive and physical decline.

After Auguste D died in April 1906, Dr. Alzheimer examined her brain. Her autopsy revealed a massive loss of neurons, and extensive atrophy in the cortex—the outer layer that is responsible for memory, language, judgment and thought. He also found the presence of tangled, intracellular fibrils and extracellular plaques, the hallmark pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Dr. Alzheimer presented these findings at a psychiatric conference in Germany in 1906—calling these abnormalities a ”peculiar disease of the cortex.” He published his findings in 1907 and over the next five years, eleven similar cases were reported in medical journals. While Dr. Kraepelin named the disease after Dr. Alzheimer, it took 70 years before the medical community began accepting Alzheimer’s as a neurodegenerative disease instead of predominantly vascular-related disease.3

Dr. Fuller’s Alzheimer’s Research

Sadly, it is only recently that Dr. Solomon Fuller has been acknowledged for his seminal role in identifying Alzheimer’s—the disease that is disproportionately killing African Americans. His work at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital laid the foundation for decades of discoveries in Alzheimer’s disease and other related dementias. At a time when almost no one knew about the brain pathology of Alzheimer's, Dr. Fuller was a leading researcher, publishing and speaking about his work as a neuropathologist.

Upon leaving the Kraepelin Lab, Dr. Fuller returned to Westborough State Hospital to continue his research and autopsies on patients with mental illnesses. Notably, in 1907, Dr. Fuller first reported on the significance of neurofibrillary tangles five months before Dr. Alzheimer, revealing one more pathological finding and basis for the debilitating cognitive symptoms that first were robbing people of their memories and eventually their lives.

In 1909, Clark University hosted a conference that was attended by 175 of the world's leading psychiatrists, including Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and many esteemed educators and physicians. Joining Freud as one of the speakers was Dr. Solomon Fuller.

In 1911, the American Journal of Insanity (later the American Journal of Psychiatry) published Dr. Fuller’s paper on unnamed plaques in the brains of seniors. Finally, in 1912, Dr. Fuller published the first comprehensive review of Alzheimer's disease in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. In this review was the case study of his own patient with Alzheimer's disease—the ninth case ever documented. Using his proficiency in both English and German, he also included the first English translation of the case of Auguste D, the woman first treated by Dr. Alzheimer. Resultingly, Dr. Fuller opined that his case studies supported Alzheimer's discovery that the clinical symptoms were not due to pre-senile dementia, but rather a distinct type of dementia.

His Later Years

“With the sort of work that I have done, I might have gone farther and reached a higher plane had it not been for the colour of my skin.”

- Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller

In 1919 Dr. Fuller left Westborough for Boston University Medical School where he again worked as a pathologist and professor. But, neither his academic acumen nor his landmark research were acknowledged equitably. He again endured employment discrimination, receiving lower pay compared to his white colleagues who were also assistant professors. And even though he was the acting head of the neurology department, he was never rewarded with a department chair nor a full professorship. It was this discrimination that caused him to retire in 1933, at just 61 years old. Upon his retirement, Dr. Fuller was appointed Emeritus Professor of Neurology. Dr. Fuller continued his career in private practice—both in neurology and psychiatry—until diabetes took his eyesight in 1944.

Among Dr. Fuller’s other proud career accomplishments was the work he did to mitigate racial disparities in mental health care. He created a training program at the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital, which opened after World War I to serve Black Veterans. Long before the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments (1932-1972), Dr. Fuller was instrumental in recruiting and training Black psychiatrists. With a properly trained mental health care team, Dr. Fuller hoped to prevent Black veterans from getting misdiagnosed and discharged, making them ineligible for military benefits.

At the age of 80, Dr. Solomon Fuller passed away due to complications from diabetes and gastrointestinal cancer. His obituary was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

His Accolades

Dr. Fuller's life and legacy have changed neurology and psychiatry. In his honor, Boston University opened the Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center, which provides psychiatric outpatient services. Boston psychiatrist & professor Charles Pinderhughes, MD was a board member who shared his thoughts on Dr. Fuller’s accomplishments:

“This remarkable man on his own initiative achieved excellence in psychiatry and neurology as a clinician, scientist, educator, and scholar at a time when opportunities and recognition… were not available to him because of his color.”

Dr. Fuller’s portrait hangs at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) headquarters in Washington, DC. And since 1969 the APA has given out an award in Dr. Fuller’s name to a psychiatrist who has significantly improved the quality of life for Black people. Dr. Annelle Primm, director of the American Psychiatric Association's Office of Minority and National Affairs told Time:

"Today there are not that many black psychiatrists who are professors in medical schools. When you put his accomplishments in that context, he was way ahead of his time.”

Conclusion

Despite racial barriers, Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller was a trailblazer who foresaw and exemplified the interdisciplinary roles of neurologists and psychiatrists to treat patients with dementia. Today Synapticure takes that same approach in treating our patients.

If you or your family members are interested in learning more about how you can receive dementia care with a cognitive neurologist or mental health support from our psychiatrists and neuropsychologists—all from the comfort of home—you can schedule a free consultation with one of our care coordinators by registering online or calling (855) 255-5917. We would be honored to help you and your loved ones.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amanda Fletcher, MD recently joined Synapticure’s Cognitive Neurology team. Prior to joining Synapticure, Dr. Fletcher specialized in treating people with Alzheimer’s and various related dementias, both in general practice and at Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers. Dr. Fletcher received her undergraduate degree in psychology from Jackson State University and her medical degree from Meharry Medical College where, just like Dr. Fuller, her first interest was psychiatry. She completed her Neurology Residency at the prestigious Barrow Neurological Institute and her fellowship training in Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry at the renowned Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health. She is passionate about addressing health disparities in cognitive neurology and is involved working in communities to help increase clinical trial interest and enrollment.

1 Livingstone College was established for black students in 1879 by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. It was formerly called the Zion Wesley Institute,

2 Alois Alzheimer was offered an opportunity to work at a new laboratory and clinic being established by the renowned Dr. Emil Kraepelin at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital at the University of Munich. At the time, Dr. Alzheimer was studying what was then called presenile dementia.

3 In 1976, a landmark editorial changed that when Dr. Robert Katzman warned the world about the coming epidemic of Alzheimer's in his editorial entitled "The Prevalence and Malignancy of Alzheimer's Disease: a major killer."

.png)